Karnak

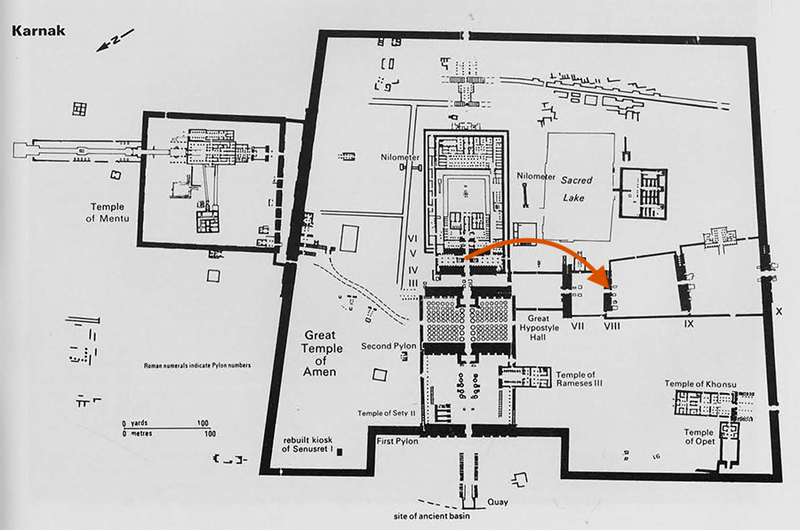

Although the remnants of Ancient Egypt have been scattered and abandoned throughout the country and former kingdom they remain to physically narrate this history. Yet, of these fragmentations, perhaps the most verbose is the ancient temple complex of Karnak. Built between the reign of Senusret I (1971-1926 B.C.E) and the Ptolemaic Kingdom (305-30 B.C.E), the "fortified village" (from the Arabic term Khurnak), while but a remnant, charter these historical periods. Thus, the respective postcards that have been selected for the exhibition are intended to represent this romanticized perspective of the periods through the utilization of various artistic and aesthetical methods.

Although several aesthetical and artistic techniques are evident throughout these postcards of Karnak, perhaps the most recognizable (within this context) are the compositional format. In which, the principal photographic studios employed the use of photography (sepia, matte, greyscale, and colorized) and illustrations (painting, watercolor, and drawing). Additionally, these studios had selected particular monuments and areas within Karnak which, in combination with the artistic styles, emphasize or rather evoke these senses of awe and wonder within the viewer. However, to properly understand this, it is necessary to conduct a literary and analytical tour of the Karnak Temple Complex.

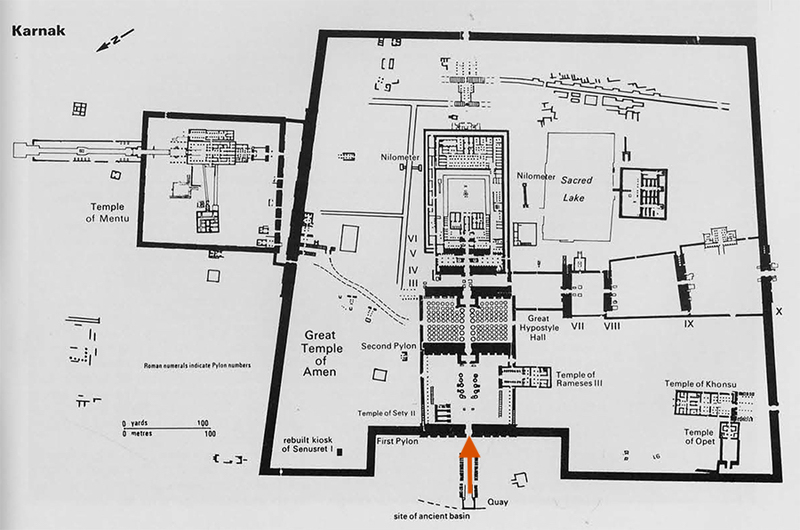

In the first postcard (Figure 2) seen in the lefthand corner, you are introduced to one of the allée des Sphinx, or otherwise referred to as the Avenue of the ram-headed sphinxes. The postcard’s artist utilizes saturated watercolors to reinforce and illustrate imbue the postcard with a sense of realism and antiquity. These watercolors best bring out the sense of realism within a painting, more so than vibrant color could. The realism is further complemented by the inclusion of a ground view perspective, as it gives the postcard recipients an semi-contempareonous depiction of how it might have looked at the time of the postcard's creation.

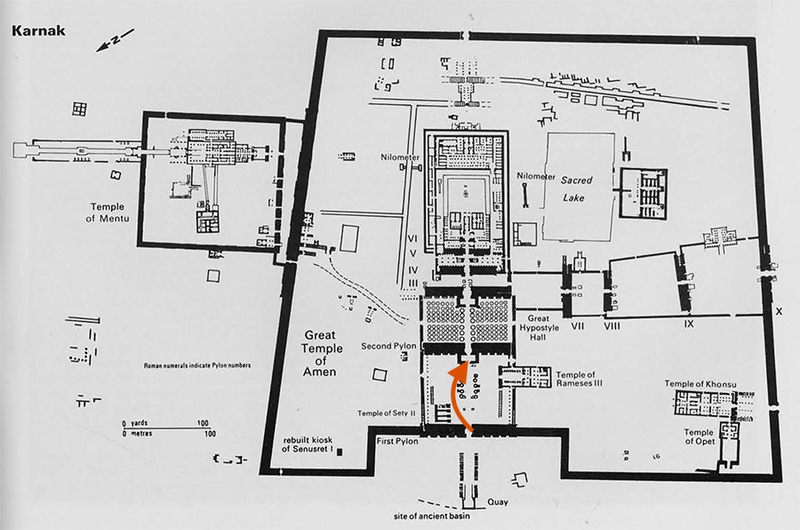

As we explore further into the Karnak complex, you enter the Great Court through the First Pylon. As you go past, the Second Pylon and the entrance to the Great Hypostyle Hall become visible (Figure 3). Unlike the allée des Sphinx postcard, the illustration composition displays starker colors and contrasts that assist in achieving this semi-chiaroscuro effect. Due to this, the contextual characteristics are indirectly projected onto a metaphysical plane. Therefore causing them to become centerpieces for other architectures to revolve around. For example, the remains of the Second Pylon, colonnade, and the sandstone structure, become the centers of visual attention. Other pictorial elements then serve to complement these structures, or even become irrelevant. The contradictory decision to use a ruined state rather than romanticized ideas of how it was seen when first constructed, implies connotations of decay and abandonment.

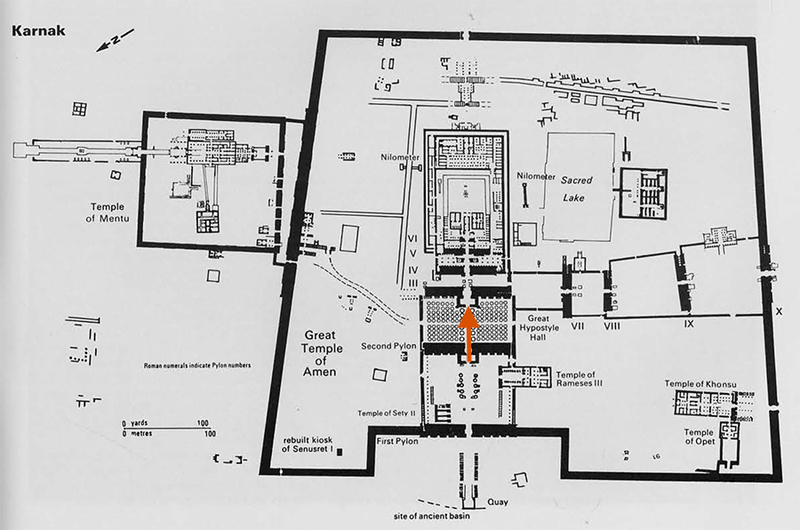

Passing through the Great Court and Second Pylon, we approach probably the most recognized and visited monument at Karnak: The Great Hypostyle Hall. While the photographer—as with the other postcards—captures these concepts of "abandonment" and "decay," the most identifiable feature is the focus on size. In which, there is a significant emphasis on these colossal monuments. This sentiment is best depicted to the left in Figure 4 showing a man dwarfed by the towering collonade. To a Western audience, this image of towering colonnades would provoke genuine astonishment as it is nothing like anything they have seen before. This displays the Eurocentric notion of exoticism as it supplements the "fantasized" and "mystical" obsession associated with Egyptomania. In which monuments of ancient Egypt transcend their functional purposes and become living embodiments of a romanticized Egypt.

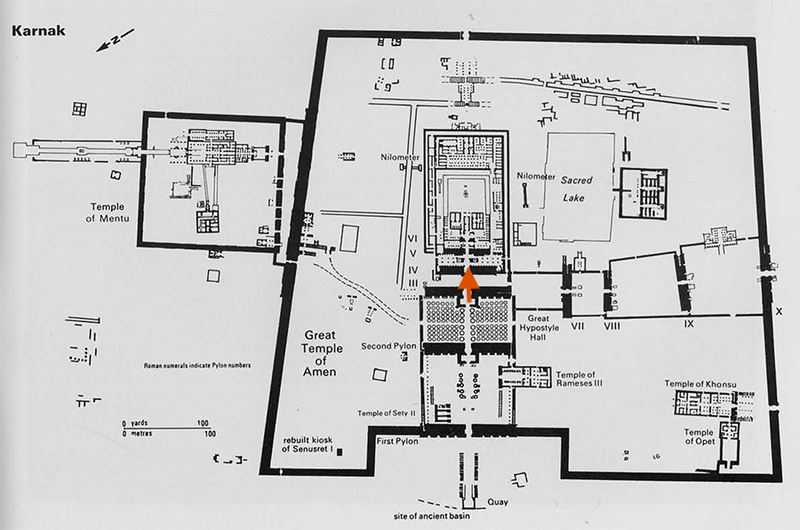

Passing through the Third and Fourth Pylons, one enters the Precinct of Amun-Re, or the largest of several temple complexes located within the Karnak Temple. As suggested by the name, the Precinct is dedicated to the principal deity of the Theban Triad Amun in the form of Amun-Re. As observed in the postcards depicting the entrance and the immediate interior (Figures 5 and 6) portray an ongoing concept of ruination via abandonment. Where the background composition is complemented, or rather accentuated by the coloristic elements. Particularly—while not illustrations—the unintended saturated appearance is devoid of pigmentation, and therefore lacks essence of vitality.

This trait is commonly seen as the tour approaches the proceeding exhibitions: the obelisks of Pharaoh Hatshepsut (1479-1458 B.C.E), her father Thutmose I (1506-1493 B.C.E), as well as the Eighth Pylon (also constructed during Hatsheput's reign). Throughout the obelisks postcard, the background composition and figures are overshadowed by these two colossal obelisks. While retaining more color albeit still saturated, the Eighth Pylon also exhibits these behaviors. In which, the local Egyptian figure serves as a reference to measure the size of the individual Pylon and the three flanking statues. Additionally, the saturated appearance—similar to the obelisks—portrays an absence of life, as color is commonly used throughout art to measure age and energy associated with that age. In relation to the other monuments depicted, these are emblematic of their antiquated age and position as remnants of a place forgotten by time. Yet, only to be "re-discovered" and "revitalized" by fetishized narratives and representations.

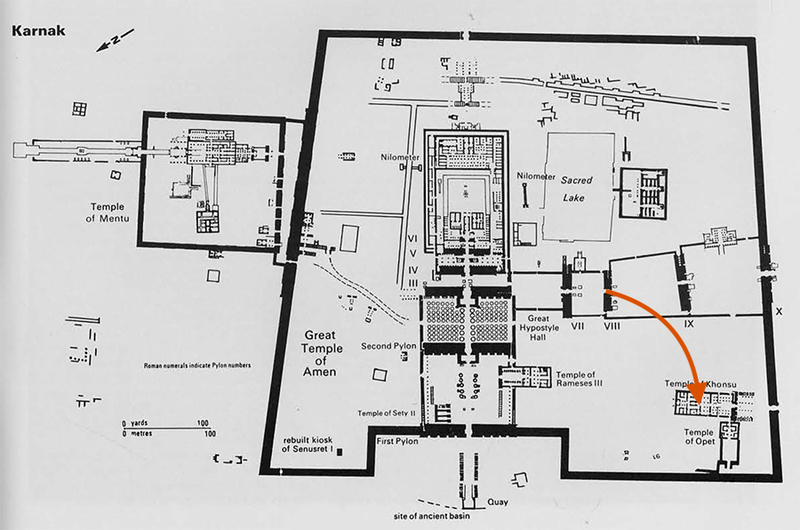

The final monument to be explored in this tour is the Temple of Khonsu located within the Precinct of Amun-Re (Figure 9). The ancient temple was first constructed by Pharaoh Ramesses III which was continually extended upon throughout the years, such as the construction of the minor hypostyle hall by Pharaoh Nectanebo I (379/8-361/0 B.C.E). The postcard also depicts Ptolemy III's colossal and elaborate gateway as it ascends above the Temple of Khonsu and the tree foliage. This gives an inherent sense of immensity meant to overtake the postcard viewer. Though the gateway’s size draws initial attention, the relief carvings embedded into the columns and roof aid in emphasizing the true mystique of ancient Egyptian construction. These reliefs are deliberately detailed to capture the viewer's attention through the subtle gold and red pigments which illuminate elegance , yet monotonous designs. It is assumed that these pigmentations are implemented in order to not only bring life to the composition, but also shed light on underlying motives this postcard illustrates. Drawing this connection throughout all the postcards, allows for various interpretations of the subjective motives for these illustrations. Color has a dual nature as it is implemented to capture the physicality of these monuments or locations, as well as the metaphysical realm of Eurocentric romanticism.

Displayed by the photographers and illustrators work in this exhibition, various physical characteristics of the Karnak Temple Complex remain consistent alongside thematic representation. The content and stylistic decisions are intended to accentuate a broader emphasis on both exaggerated physical and metaphysical understandings. These postcards underline Eurocentric connotations, which further contributes to the romanticized perception of ancient Egypt. Though appearing as seemingly average postcards, they heavily reflect the imperialistic and socio-political roots of Egyptomania in popular culture. From these observations, one can infer that the authors of these Karnak postcards are not interested in presenting an accurate depiction of history, rather they are only concerned with painting romanticized imaginations. Thus, the Karnak as depicted in the respective postcards, is figuratively not the Karnak Temple Complex of ancient Egypt, rather it is a Eurocentric fantasy.