Losing a Buddy: An Army Engineer's Experience of Viet Nam

Introduction

An oral history with Mr. Dennis Phelps, born on the 21st or 22nd of May 1949 in Ogden, Utah. He was drafted to participate in the Viet Nam War as an Army Engineer in 1969, where he would subsequently be deployed in 1970 to 1971. He was a part of the 103rd Army Engineers and the 169th Engineer Battalion. Phelps describes his experiences in great detail, including his time in Viet Nam as an engineer; a rare topic that is often overlooked. He also discusses the camaraderie between himself and his comrades, as well as the time they spent together: both the good and the bad. Phelps also discusses the trauma he faced and how he managed it during his tour in Viet Nam and upon returning to the United States. The interview also sheds light on how Phelp's adjusted to civilian life and how he was treated by others as a Viet Nam veteran. Phelps' also provides his perspectives on this treatment and the war itself and how they have affected his life.

Early Life

Dennis Phelp's was born in 1949, four years after the end of World War II. He had two parents: a mother who stayed at home to take care of him and his two brothers and his father who was a construction worker. He described his parents to be hard workers who refused to accept charity and embraced hard work in order to help others; an idea that would be instilled in Phelps for the rest of his life. Phelps was also the first individual in his family to achieve a high school diploma and became a certified welder by the age of 19 as well. This adeptness would guide Phelps' career in the army as an engineer when he was drafted in in 1969 to serve in the Viet Nam War.

Training Background

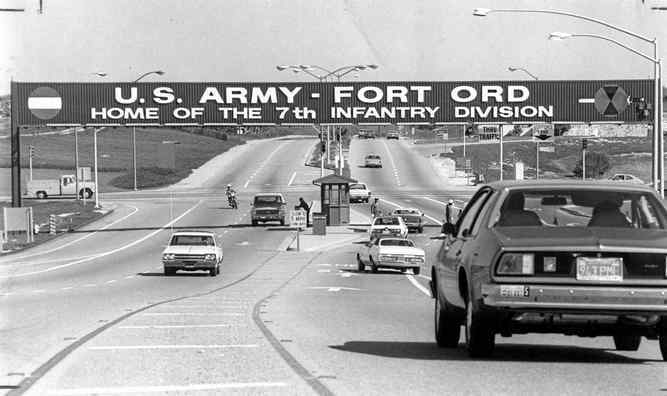

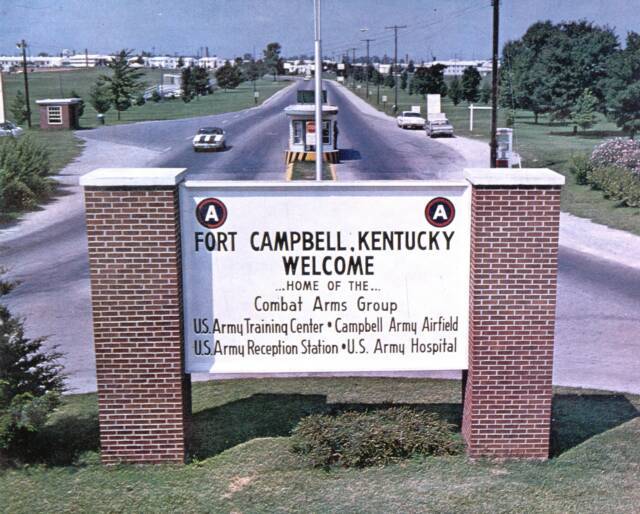

Phelps completed his basic training in Fort Ord, California where he learned how to operate weapons and standardized equipment required by all personnel. He states that a person learned to become "really physically fit". Other oral history accounts echo this sentiment, stating that the training was extensive and spanned over the course of six months. Phelp's then was transferred to Fort Campbell, Kentucky to teach welding to new recruits due to his Military Occupational Specialty as a welder. He found that assessing a person's aptitude for a task was necessary in helping them reach their fullest potential during the teaching process.

Phelp's Viet Nam War Experience

After completing his training, Phelps was deployed in Viet Nam in August of 1970 in Nuy Li* of the Long Khanh province (present day province of Dong-Nai). When asked about his first impressions of Viet Nam, he immediately recalled the smell, calling it the "smell of death". He initially arrived in Cam Ranh Bay, and then stayed in Bien Hoa for two days in transit barracks until he was assigned to the 103rd Army Engineers. His experience matches that of other veterans who also share the same memory of recalling the smell. One account of an engineer named William Badger also mentioned the brutal monsoon season which hindered the quality of life in the camps, which Phelps also mentioned when inquired about the monsoon season. Phelp's duties were a difficult, but necessary means to ensure the safety and contentment of the soldiers in the camps. Phelp's primary duties included burning excrement, detonating mounds hindering travel, guard duty, and repairing vehicles that were damaged in combat. One of the more interesting tasks he undertook was building a water heater that would provide hot water to the entire camp, which was a commodity that the compound lacked. While the tasks seemed mundane and menial in nature, they highlight the often overlooked nature of the convenience of everyday goods one takes for granted. Phelps' duties were similar to that of other engineers in Viet Nam in the sense that they were crucial to survival. One account of a refrigeration engineer, Greg Hocking, states that lack of refrigeration was an immediate problem which led to the imminent construction of a refrigeration building. Like refrigeration, repairing equipment and providing necessities were vital concerns which Phelps and other engineers alleviated during the war. Phelps also stated that he and his fellow engineers would create anywhere from sixteen to eighteen thousand yards of gravel weekly, which were used for gravel mines.

*Nuy Li could not be found on the map of Viet Nam, so the name may not be accurate.

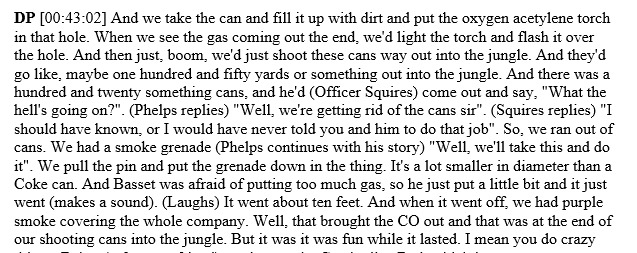

While stationed in Nuy Li, Phelps experienced both difficult and lighthearted moments. Most of his stories of Viet Nam revolved around fond memories of his "buddies" Bob Basset, "Baker", and "Greene". One of these lighthearted moments was when he and Basset were instructed to get rid of the cans lying around the camp. Their solution to this issue was to shoot them into the jungle:

Phelps mentioned that these kinds of activities helped maintain his sanity there, as he learned about the fragility of life. One of his difficult experiences was when he wounded an enemy, but never discovering if he was alive or dead afterwards. He stated that he greatly pondered on the idea that the man's children would wonder where their father was, and that he would potentially never see his children again. A revelation he discovered as a result of this was that hatred was a learned trait, and that everyone bled the same regardless of size, color, or social status.

Losing a Buddy

The most difficult moment in Viet Nam for Phelps was the death of his friend Ray Desmond. On April 5th, 1971, Desmond was killed by shrapnel from a command detonated mine on the way to Long Binh Post. Phelps had sent him on an errand in his place in order to fix Desmond's damaged vehicle. As a result, he was killed as a result of of the exchange of duties. Knowing that Phelps thoroughly enjoyed the time he spent with his buddies, it was especially diffficult for him to lose someone he had a deep connection with, especially since Desmond had taken his place on that fateful day. It was an event that left Phelps with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder along with survivor's guilt that would follow him for more than fifteen years.

Returning Home: Coping with Trauma and Treatment of Veterans

After Phelps returned home to the United States in June 1971, Phelps struggled with PTSD and depression. He often contemplated suicide, as Desmond's death had dealt a heavy toll on him. It was not until he visited Desmond's family at the portable Vietnam War Memorial at Rose Hill where he was able to find peace. Phelps spoke to Desmond's mother, who stated that she wanted to "adopt him to take her son's place". It was an event that would serve as a catalyst for Phelps' healing and personal redemption.

Treatment from civilians back home, however, was poor. Upon his return home, Phelps experienced exclusion from the American Legion and other establishments that were not friendly to Viet Nam veterans. In addition, he received heckling for his service by frequenters from a restaurant he often visited with friends, leading him to cease his activity there. Feeling that the rest of society perceived him as a baby killer, Mr. Phelps believed his family was the only group who accepted him for who he was.

This perspective aligns with the experiences of other veterans. James Bussey, another fellow veteran, explained how people assumed he was a "baby-killer" and drug user, with even a few of his acquaintances believing he was a "bad" person. Another former Marine rifleman named James Morris who was in the country from 1969 to 1970 did not personally experience anti-war sentiment, although he heard stories from other veterans about this poor treatment. He mentioned that when he returned from Viet Nam, however, some of his friends were "distant" towards him, thus changing their friendship.

It is important to mention that some studies showed that many veterans did not experience the same treatment as Phelps or Bussey, and were able to successfully integrate into civilian life. as shown with James Morris. However, it is equally important to mention the unique experiences each veteran has and the impact they have on their lives years later.

Regardless of his reception coming home, Phelps felt immense pride in his service. He become emotional, discussing how he would do it all over again; a sentiment shared by many other veterans. Through his pain, he was still able to feel pride in his actions which is something that drives him today.

Giving Back

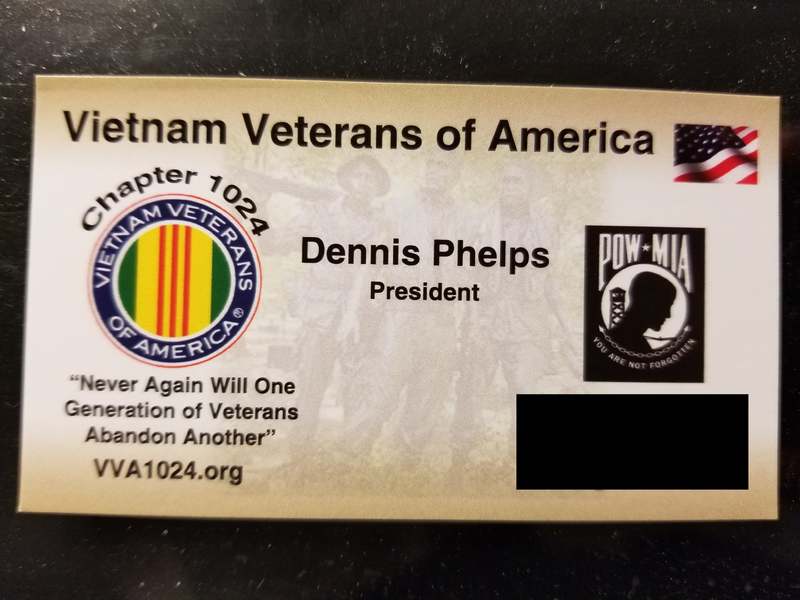

For fifteen years, Phelps was closed off and unwilling to speak about his experience as a veteran or even disclose that he was a Viet Nam veteran. However, as the years went by, his perspectives changed as he learned to feel pride in his service and to forgive himself for Desmond's death. These factors along with his willingness to help others have compelled him to assist those who struggled with the same difficulties as he once did. Phelps has contributed to various veteran's organizations including his local chapter of Vietnam Veterans of America, of which he is the current president. He also fought for benefits for veterans of both the Viet Nam and Korean War in an effort to improve their quality of life. In addition, he helps veterans transition to civilian life with a veteran's helicopter ride program that retrieves them from their last deployment. When inquired about his thoughts in the present day, Phelps replied that he did what he did, not to gain anything, but to help others. And by sharing his story after years of silence in order to aid the future generation, he continues to be that helping hand. Phelps currently resides in Orange, California with his wife.

Full Transcript

Keywords: 103rd Army Engineers, 169th Engineering Battalion, Dong Nai, Military Occupational Specialist (MOS), mobile Vietnam Memorial Wall, Nuy Li, papa-san, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), returning home, Veterans Affairs, welding

Bibliography

Badger William. “William Badger Collection (2073) Finding Aid, William Badger Collection, Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive.” Interview by Gary Hayes. Texas Tech University. https://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/virtualarchive/items.php?item=20730000000.

Laufer, Robert S., M. S. Gallops, and Ellen Frey-Wouters. “War Stress and Trauma: The Vietnam Veteran Experience.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 25, no. 1 (1984): 65–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136705.

Carbonella, August. “Where in the World Is the Spat-Upon Veteran? The Vietnam War and the Politics of Memory.” Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 49–58.

Dean, Eric T. “The Myth of the Troubled and Scorned Vietnam Veteran.” Journal of American Studies 26, no. 1 (1992): 59–74. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27555590.

Johnson, Loch. “Political Alienation among Vietnam Veterans.” The Western Political Quarterly 29, no. 3 (1976): 398–409. https://doi.org/10.2307/447512.

McNally, Richard J. “Memory and Anxiety Disorders.” Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences 352, no. 1362 (1997): 1755–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/56699.

Bussey, James, interview by Richard Burks Verrone, The Vietnam Archive Oral History Project, November 11, 2002.

Butch Morris, James, interview by Kim Sawyer, The Vietnam Archive Oral History Project, February 20, 2000.

Melton, Allison R., "Oral History for Greg Hocking - Engineer during Vietnam War" (2016). Vietnam. 23.